Quality doesn’t happen by accident - Robert Boschs view

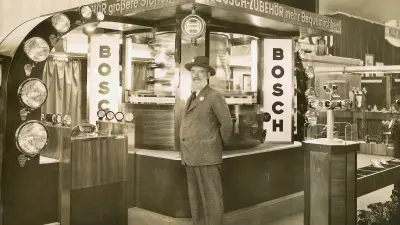

Robert Bosch standing at booth, 1931

Robert Bosch did not leave behind much in the way of recollections or quotes, but in the few statements of his that have survived, the entrepreneur repeatedly comes back to one key concept in his corporate philosophy: quality.

Striving for excellent quality at all times in his products and business practices was one of Robert Bosch’s guiding business principles. At the same time, quality was an ongoing challenge, a constant in the company’s history that accompanied Robert Bosch from the earliest days of his first small workshop in the fall of 1886.

Robert Bosch’s retrospective and plea

Looking back on the company’s history, it was important to Robert Bosch to make quality the key concept of his corporate philosophy. During the rise of his company, which had started out small, but also during periods of crisis, quality never lost any of its importance. It was at least as important as other key entrepreneurial concepts such as innovation.

In 1919, Robert Bosch wrote the following in the Bosch-Zünder employee newspaper: “It has always been unbearable for me to imagine that someone could inspect one of my products and find it inferior in any way. For this reason, I have constantly tried to deliver only products that withstand the closest scrutiny — products that are, so to speak, the best of the best.”

This quote also provides some insight into the personality of Robert Bosch, the entrepreneur who proclaimed that the quality of his products was his core competence. His products, as we can deduct from this passionate plea, stood out from the goods of other manufacturers in each phase of the company’s development. While consumers might end up paying a bit more for Bosch products, they could rely on the products’ durability. By taking this considered approach, the entrepreneur and his sales strategists had an effective means of countering price as an argument in favor of rival products.

Basic concerns

Today, we would place this approach within the context of sustainable business practices, but for Bosch customers — be it in 1886 or 1919 — there were very basic concerns at the heart of product quality: not having to sit in the dark because of power outages, not being struck by lightning because of faulty lightning rod assembly, and not getting stranded in the middle of nowhere because the ignition had given out. This kind of failure to deliver on quality would probably have spelled doom for Bosch’s small workshop in the 1880s or 1890s, or even for the medium-sized “Robert Bosch Electrical Engineering Plant” in the early years after the turn of the century. Thus, Bosch’s insistence on delivering “the best of the best” was certainly a crucial factor in guiding the small enterprise out of the crises that it repeatedly encountered in its early days. Bosch’s generally pedantic nature probably also came in handy when it came to managing crises. In the early workshop years, he is said to have become very vocal about poor work results. One associate on board from the very beginning refers to these outbursts in his memoirs as a “cathartic storm.”

1886: The first workshop

In November 1886, 25-year-old Robert Bosch opened his workshop in a courtyard in Stuttgart with one foreman and one apprentice. During the second half of the 19th century, urban quarters sprung up in the cramped topography of Stuttgart — capital of the Kingdom of Württemberg — featuring street-facing buildings with closely built courtyards behind them. In the 1870s and 1880s, a large number of craftsmen opened up shop in these courtyards. Bosch’s “Workshop for Precision Mechanics and Electrical Engineering” had to brave relentless competition from a myriad of small courtyard businesses, which meant that the young entrepreneur had his hands full keeping the company above water – he later referred to this period as “a shambles.”

So, he thought, what could be more beneficial for the development of the company than achieving good results that would generate recommendations? If he was largely offering the same products as numerous other small entrepreneurs, his results had to be noticeably better than those of the competition.

Bosch did not really have any alternative. Just like his competitors, Bosch was busy with repairs, the installation business, maintenance, and replicating precision and electrically powered products. This was supplemented by a smorgasbord of hand-manufactured products: electric lights, intercom systems, and lightning conductors, as well as “exotic” products such as typewriters for the blind and cigar cutters. His product range could hardly have been more colorful, especially as it primarily consisted of one-off products made to special customer requirements.

1919: Crisis and new beginnings

The year after the First World War — from which Robert Bosch was looking back on his beginnings in his 1919 article for the Bosch-Zünder — was a bitter year for his company. The capitulation of the German Empire at the end of the First World War had dramatic economic consequences. Bosch, who had focused on international business early on and whose company had conducted most of its sales — in 1913, 88.7 percent — outside of Germany in the years before the First World War, saw his global network of foreign companies, production facilities, authorized dealers, and business partners fall into ruin.

The allied war opponents expropriated a majority of Bosch’s properties in those countries. Starting again internationally at this time would only be possible with the highest quality – because German products were not exactly popular in France, England, and the U.S.

Not by accident

For this reason, it is no accident that, in 1919 of all years, Robert Bosch was reflecting on the beginnings of his company — on the uncertain time he had spent as a young precision mechanic without any regular customers. In one of the worst economic periods for his company, he once again invoked his concept for success: that only the “best of the best” would be allowed to leave his workshop. And, of course, he was not expressing this credo without ulterior motives. The Bosch-Zünder, deliberately named after the magneto ignition system for automobiles that had capitulated Bosch from his life as a workshop tenant into the world of manufacturers, had just been launched as an employee newspaper. The company founder used this medium to appeal to all of his associates and addressed what was important to him and what he wanted to see “entrenched” in his workforce.

However, keeping up with the self-imposed quality requirements was extremely strenuous for all the company’s associates. In what had been the world's largest foreign market until 1914, the U.S., properties went to a sequestrator after 1918, who sold the confiscated factories and sales offices. A U.S. company was now distributing earlier Bosch products, which were still being built in the same way, under the name “American Bosch.” However, liberties were taken with the quality standards that had applied under Bosch’s direction, and there was a deterioration in the reliability and durability of the ignition systems, starters, and car generators. When Bosch started buying back his U.S. properties in 1927, this became a problem. The Bosch brand suffered heavily under the diminished quality of the products that had been labeled with “Bosch” in the U.S., as the separation from the Bosch parent company and the lack of entrepreneurial and technical expertise of the U.S. sequestrator had meant that quality controls had either been too lax or had taken place too seldom.

Quality is not everything, but it is crucial

This example shows that the pursuit of high manufacturing and product quality entailed a myriad of challenges that the company founder and his management, and after 1925 his successors, had to adapt to time and time again.

Curiously, in the early years, the company’s quality concept was much broader than it was after 1900, when Bosch rose to become a mass manufacturer for the automotive industry. In the beginning, both the manufactured products, and customer support and service had to be of high quality.

This changed with the event of mass production, which saw Bosch increasingly pulling back from the service sector – back then the installation business – after 1900. Those who only sell their own products – so the logic behind this business concept went – do not need to have any qualities in other business sectors.

Quality and services

But this attitude was to change at Bosch, and for good reason. It is interesting that service quality came back into play later on, because making a quality impression was not just about the product, but about everything else being offered around the product. Bosch paid tribute to this with the founding of sales offices in major cities and the international establishment of “Bosch-Dienste” (Bosch Services), which began spreading out of Hamburg in 1921. The concept was relatively simple: automotive and motorcycle workshops that were able to prove that they fulfilled certain criteria pertaining to their equipment, size, and clientele were allowed to call themselves “Bosch-Dienste,” were provided with testing and repairs equipment, and could buy Bosch replacement parts for retail at special conditions. Customers had a point of contact where they could receive advice and have their Bosch products serviced — or exchanged in the event of defects.

It was this approach that took the components that made up the impression of quality and turned them into an overall concept. It became the successor to the installation business that had previously been relinquished, translating the old know-how into a modern strategy. From that point on, this strategy flanked the sale of products and applied Bosch’s commitment to quality to the increasingly important field of service. Conveniently, the brand was simultaneously becoming more visible.

Résumé

But in spite of everything, in the 1920s, good quality was no longer enough of a sales criterion if it was not sufficiently visible or communicated properly. The same applied to Bosch. For this reason, the company went on the offensive with advertising, which, at this point in time, operated using sophisticated, artistic images of Lucian Bernhard and slogans like “Mit Bosch gerüstet — gut die Fahrt!” (Equipped with Bosch — a good journey!).

We do not know to which extent the company founder was involved in the development of customer service or the advertising strategy, but Robert Bosch knew that those who offer good quality had to advertise it. However, his prioritization remained an unmistakable part of his corporate philosophy: “I myself know that I have made a greater impact with the quality of my products than with advertising.”

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz