Why we need to work on all powertrain types

2024-09-17

Normally, a commercial-vehicle trade fair and Formula 1 have little in common. In today’s world at least, 40-ton trucks with slick tires and ceramic disc brakes are still the exception. But if you look at the industry as a whole, the current situation is actually a bit like the start of the Grand Prix season. The race for the right powertrain technology for commercial vehicles is still wide open: it’s difficult to estimate how fast infrastructure will develop, and the regulatory framework is still the subject of heated debate.

by Stefan Hartung

chairman of the board of management of Robert Bosch GmbH

The conditions under which the race is starting are far from easy. Each powertrain technology is still following the safety car, so to speak. Anyone who dashes ahead will have a problem; anyone who hesitates too long will find it impossible to catch up. Winning is all about getting the timing of the sprint just right.

There’s certainly no doubt about where the finish line in the race for the right powertrain technology for commercial vehicles lies: we all want commercial vehicles that are as climate neutral as possible. And we all want freight transport that’s affordable and doesn’t place an undue burden on freight forwarders or consumers.

This goal is within our reach. To achieve it, we need political clarity, incentives for investment — and technological freedom. Because although future powertrains will be more climate-friendly than today’s, we won’t see the same ones being used everywhere.

20%

of all newly registered commercial vehicles heavier than six metric tons will have a battery-electric powertrain in 2030.

For the moment, it looks as if various powertrain types will coexist. Our moderate scenario assumes that, globally, around 20 percent of all newly registered commercial vehicles heavier than six metric tons will have a battery-electric powertrain in 2030, while fuel cells will have a share of around 3 percent.

Five years later, in 2035, at least one in three trucks will have a battery on board, and one in ten will feature a fuel cell. We will then also see hydrogen engines on the roads and in off-highway vehicles, although in considerably smaller numbers.

Of course, the actual course of development will depend on the respective application and region. But the message is clear: as soon as the markets or legislation turn noticeably in one direction, we as an industry must be able to ramp up our production efficiently for all powertrains.

Climate-friendly powertrains will only become established, if they make financial sense

However, it’s no longer under the hood that all the truly decisive variables for the freight transport of the future are to be found. What used to be largely a question of automotive technology has now become a general issue for society. Ultimately, anyone buying a commercial vehicle really wants to know three things above all. First, will the new technology lead to lower overall costs? Second, is the new technology competitive? Third, is the necessary infrastructure in place? The answers to these questions aren’t solely technological, but political as well.

Climate-friendly powertrains will only become established if they make financial sense. For freight forwarders, for the economy, for society. And that’s true all over the world. It’s up to policymakers to help get things moving.

The first step should address cost. It would take very little effort for policymakers to set a clear signal here. For example, they could encourage low-emission vehicles through tax incentives and by exempting them from levies such as the truck toll, at least for a few years.

Second, it’s clear that massive investment in infrastructure is needed. Especially in Germany and elsewhere in Europe, not enough is being done. There are too few charging stations, too few hydrogen filling stations, too few renewables. Subsidy programs aren’t being implemented consistently enough, there’s a lack of incentives for private investors, and the overriding goal is too often obscured by squabbles over special interests. And unfortunately, trucks can’t run on hot air alone yet.

This means — and that brings me to my third step — that we need more pragmatism and more openness. We should finally start making use of our many options instead of endlessly arguing about the one-and-only best course of action. When all is said and done, it will be the customer who decides anyway. And in the commercial-vehicle sector in particular, most customers have no time for wishful thinking. The only thing that matters is the TCO.

Comprehend diversity and cater to every application in the best possible way

Of course, this is about much more than just logistics companies’ profitability. It’s about affordable food, affordable public transportation, and the competitiveness of industry. And for that reason, it’s better not to rule out certain solutions and ideas from the outset.

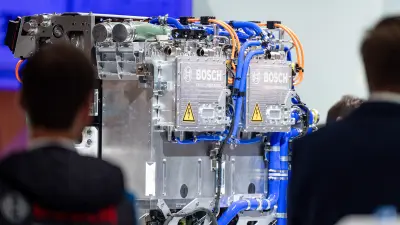

We need to work on all powertrain types and make each of them more efficient. That includes batteries, fuel cells, the hydrogen engine — and, naturally, state-of-the-art combustion engines. Especially in view of the 62 million heavy trucks already on the roads globally, synthetic fuels can also play a major part in mitigating climate change. They are another solution we should definitely not do without.

At Bosch, we believe it’s our responsibility to comprehend this diversity and to cater to every application in the best possible way. It’s not just one single technology we are focusing on, but instead the future of mobility as a whole. And that goes for both passenger cars and trucks.

That’s why we’re currently reorganizing Bosch’s commercial-vehicle activities: we’re bringing important skills and expertise together in a new business unit, we’re merging systems engineering for powertrains with that of other vehicle components, and we’re establishing centralized portfolio and product management for commercial and off-highway vehicles. And all this under the purview of a single chairperson for the entire market segment. This role will be assumed by Jan-Oliver Röhrl, who is currently a member of the executive management of our Power Solutions division with responsibility for manufacturing. We’re convinced that this new setup will offer a clear benefit to our customers — and enable us to be even more successful.

But, like any 40-ton truck, the markets won’t be going anywhere without a suitable drive. And the best way to drive growth and success is still with innovation. At Bosch, we certainly have some ideas for the truck of the future.

In India, we’re working with several OEMs on hydrogen engines for heavy trucks. The first test vehicles are already on the roads and their market entry is expected in the coming year. Among other things, Bosch supplies the injection system, sensors, tank valves, and control units together with the appropriate software for the hydrogen powertrain.

For the Chinese market, an eAxle for heavy commercial vehicles weighing between 18 and 49 tons has already gone into volume production. This rigid axle is available in several versions, each featuring a fully integrated electric motor, transmission, clutch actuator, inverter, and differential. The solution is efficient, helps bring down operating cost, and is suitable for both battery-electric vehicles and those with fuel-cell electric modules. Joint projects with eight customers are currently underway in China.

In the U.S., together with our partner FirstElement Fuel, we’re currently testing a cryopump that compresses up to 600 kilograms of liquid hydrogen per hour. This could be a game changer. Why? Because within ten minutes, trucks will then be able to fill up with enough hydrogen for the next 1,000 kilometers. A range like this is on a par with diesel — and for many truckers and fleet operators, it’s an important argument for switching to hydrogen.

Commercial vehicles will become software-defined vehicles

However, it’s not just the powertrain system that’s set to see significant change in the commercial vehicles of the future. They will also have completely new driver assistance systems and much more software on board. First, this is because the economic benefits of automated driving will be seen more quickly in trucks than anywhere else. And second, because trucks and vans need to be updatable — not least because of the growing number of connected services and solutions for fleet management.

In this respect, commercial vehicles will soon become software-defined vehicles, with ever fewer — but more powerful — vehicle computers.

Today I’ve mainly talked about the issue of powertrains in this article. The reason for this is simple: the ongoing transition in mobility will only be successful if people are willing to accept and support it. I’m certain that many people welcome the goal of climate neutrality in principle. At the same time, however, I also believe that the degree of consensus strongly depends on whether or not people feel they can decide for themselves which path they take to get there. This is just as true for freight forwarders as it is for individual consumers buying cars.

And as manufacturers and suppliers, we bear a particular responsibility here. For change to be accepted, it’s vital that the operation of trucks of all sizes and off-highway vehicles be reliable and competitive both during and after the transformation — in ways that are perfectly tailored to the respective application, region, and economic situation.

That’s why we need a variety of powertrain technologies. That’s why we need technological neutrality. And we need a discourse that neither paints everything black nor sets out to polarize. A rethink works better when we broaden our horizons instead of narrowing them.